Processes#

Command |

Action |

|---|---|

|

Show running processes |

|

Monitor the machine resources interactively |

|

Show the jobs in the current shell |

|

Put a stopped job into the background |

|

Put a job into the foreground |

|

Send a signal to a process (sometimes stopping it) |

|

Kill a process by name |

|

Turn off the computer |

When a program executes it becomes a process. If a program on disk is a book then reading it is a process. Linux allocates the computer’s resources to processes as they need them. There are three categories of resources that a process uses:

CPU time. A process consumes processor time as it executes. A CPU can only execute one process at a time, so the amount of compute time is limited by the number of CPU cores in the computer.

Memory. Programs must be loaded into memory before they can execute and usually request additional memory to do their work. Memory is a limited resource, when it gets scarce computers run very slowly.

File Handles. File handles are for more than just files. All I/O functions on Linux are performed using file handles, including network I/O and communicating with device drivers.

This introduction will show you how to control process execution, examine process resources and understand how Linux manages the resources of the computer.

Controlling Processes#

A process is a running program. Processes use the CPU to execute instructions. The processes we’ve used so far in the class have usually executed quickly and finished, causing the shell to return to the prompt. What happens when you use the cat command with no arguments?

$ cat

The cat program reads from stdin and keeps running until you tell it to stop. So far, you’ve done this in two ways.

Ctrl-dsends the “End of File” character which tellscatthat there’s no more input.Ctrl-csends the interrupt signal (SIGINT) causingcatto quit.

Now let’s use the ping command. The ping command helps administrators diagnose network problems. It sends a “ping” packet to a remote host and waits to hear a “pong” back. Try using the ping command to send pings to enterprise.cis.cabrillo.edu:

$ ping enterprise.cis.cabrillo.edu

PING enterprise (192.168.100.12) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=1 ttl=63 time=0.857 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=2 ttl=63 time=0.508 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=3 ttl=63 time=0.418 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=4 ttl=63 time=0.440 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=5 ttl=63 time=0.344 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=6 ttl=63 time=0.348 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=7 ttl=63 time=0.453 ms

64 bytes from enterprise (192.168.100.12): icmp_seq=8 ttl=63 time=0.398 ms

^C

--- enterprise ping statistics ---

8 packets transmitted, 8 received, 0% packet loss, time 7149ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 0.344/0.470/0.857/0.156 ms

The ping program will not quit until you tell it to stop with Ctrl-c.

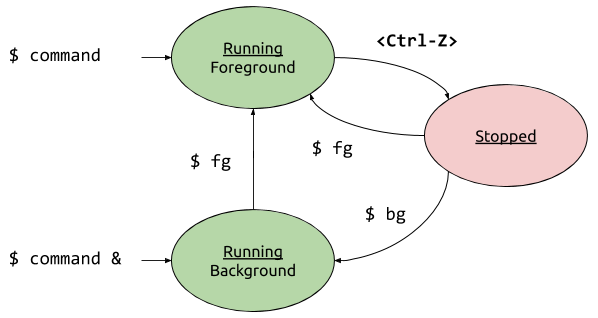

The drawing below will help you remember the states a process can be in:

Job Control Demonstration#

Below you can see that I put top in the background with the Ctrl-z key combination. Then brought it back into the foreground with fg. In the top terminal I killed it using the kill command.

I split the screen using a program called

tmux. Try it!

pstree and top#

The pstree command makes a nice view of processes:

$ pstree

systemd─┬─accounts-daemon───2*[{accounts-daemon}]

├─atd

├─cron

├─dbus-daemon

├─irqbalance───{irqbalance}

├─login───bash

├─lvmetad

├─lxcfs───7*[{lxcfs}]

├─master─┬─pickup

│ └─qmgr

├─networkd-dispat───{networkd-dispat}

├─polkitd───2*[{polkitd}]

├─rsyslogd───3*[{rsyslogd}]

├─sh───node─┬─node───10*[{node}]

│ ├─node─┬─bash

│ │ ├─node───6*[{node}]

│ │ └─16*[{node}]

│ └─11*[{node}]

├─sshd─┬─sshd───sshd───bash───sudo───su───bash───pstree

│ ├─sshd───sshd───bash───sudo───su───bash

│ ├─sshd───sshd───bash─┬─bc

│ │ └─2*[less]

│ └─2*[sshd───sshd]

├─3*[systemd───(sd-pam)]

├─systemd-journal

├─systemd-logind

├─systemd-network

├─systemd-resolve

├─systemd-timesyn───{systemd-timesyn}

├─systemd-udevd

└─unattended-upgr───{unattended-upgr}

If you run pstree with the -u option it shows you who owns each of the processes. You can see processes running in real time using the top command.

The top command gives you lots of useful information about the system.